Hong Kong as a Rosetta Stone for US-China Relations

Lenin famously said “there are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks where decades happen.”

In May I spoke at the Young Presidents Organisation of Hong Kong. I covered a number of subjects but didn’t give myself enough time to discuss Hong Kong itself. So I am writing this for them.

Recently Western journalists and anti-China Hong Kong politicians have lamented that Hong Kong will never be the same as a new society law was introduced. As a global futurist and a Hong Kong permanent resident, I have often seen Hong Kong as a kind of rosetta stone for the relationship between China and the US.

I first visited Hong Kong in the early 1990s when it was a bustling commercial hub and British colony. I fell in love with its vibrancy, Chinese culture and cuisine, and of course the melting pot of East and West. I was both proud of the legacy the British rule had left with a civil service and infrastructure that was in some ways better than Britain, and a little uncomfortable with the history that the land was seized by the British in 1841 in the first Opium Wars .That all said, it was my gateway to Asia and I was overjoyed at having discovered it. I have been based out of Japan, Korea or Hong Kong ever since, whilst doing business predominantly with the USA – another country which I love and has inspired me.

When I first visited Hong Kong, China’s GDP was only $619bn. , and by the time I moved there in 2006 it was in the process of displacing the UK as the 5th largest economy in the world. By the time I was issued a permanent residency 8 years later, it was the 2nd largest economy and prominent venture capitalists were saying that Beijing was the only potential rival to Silicon Valley in the world.

One might say that Hong Kong is the only place on the planet where 2 these civilizations meet: the US-led West and China. Hong Kong retained much of the laws and ways of doing things it had under British rule, and many people consumed Western media. But of course, it was now part of the People’s Republic of China and Chinese flocked in greater number to work and live there.

When I lived there in the run up to the GFC of 2008/9, we were in a boom period as China had joined the WTO. Whilst I was a friend of China – and was a lonely voice recommending people buy Chinese stocks in about 2004 – I must admit I was a little concerned about the rush of Western corporations to put all their manufacturing operations out there. Like James Goldsmith, the British entrepreneur who wrote The Trap I was worried whether it was a little too much and might not only result in a fall in long term competitiveness of the West, but also a fall in social harmony. So I was both enjoying having front row seats to the China miracle and worried about the future prospects of the West.

The Cracks

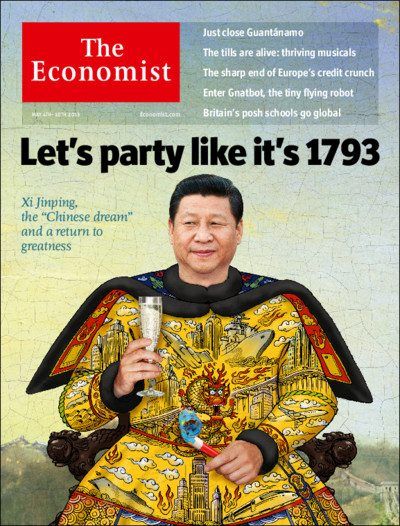

In March 2013 Xi Jingping became President of the People’s Republic of China. He was more assertive than his predecessor and the relationship started to shift. The Economist magazine ran with the headline above and wrote:

“IN 1793 a British envoy, Lord Macartney, arrived at the court of the Chinese emperor, hoping to open an embassy. He brought with him a selection of gifts from his newly industrialising nation. The Qianlong emperor, whose country then accounted for about a third of global GDP, swatted him away: “Your sincere humility and obedience can clearly be seen,” he wrote to King George III, but we do not have “the slightest need for your country’s manufactures”. The British returned in the 1830s with gunboats to force trade open, and China’s attempts at reform ended in collapse, humiliation and, eventually, Maoism.”

China has always wanted to overturn the century of ‘humiliation’ by the Western powers, and now as the second largest economy in the world it was going to be more assertive. Deng Xiaoping followed and advised Chinese leaders to ‘Hide your strength, bide your time.’ President Xi reversed this.

Domestically Xi also cracked down on corruption, but there has been a feeling that the administration has been far more authoritarian as well. This is quite openly discussed by the Beijing elites in the restaurants and teahouses in Beijing and on trips outside China. Funnily enough, though, in some ways one feels that its easier to speak one’s mind in Asia, including China, nowadays compared to the US where there is significant groupthink and political correctness. Sam Altman commented on this a number of years ago and confirmed my experience.

America First

The first real break started around 2015 with President Obama on his way out, and the US Presidential election campaign heating up. US politicians increasingly grappled with the dying working class (and even middle class) in the post GFC world. President Trump targeted China and the trade imbalance as part of his ‘Make America Great Again’ slogan, hoping to get investment back onto US soil. At the same time, many Western commentators and think tanks began to criticise China for becoming geopolitically hawkish outside and more restrictive with censorship at home.

It didn’t take long for the clouds to get darker for US-China relations as many American politicians started to voice concerns about the threat of China’s rising technology sector. President Xi established a national strategy for China to become self-reliant in technology and surpass the US as a global high tech leader. It made major moves in key industries of the future from AI (perhaps inspired by the Alpha Go breakthrough by British/US firm Deep Mind) to quantum technology, such as the Chinese National Lab for Quantum Information Sciences. R&D expenditures in China were edging closer to the USA according to the National Science Foundation (https://www.nsf.gov/nsb/sei/one-pagers/China-2018.pdf). There were a number of moments which I was wondering might be identified as Sputnik moments, referring to where the US galvanised all of its resources on the Apollo program after the USSR beat the USA into space. Perhaps military intelligence and the Pentagon were shaken by the Chinese advances in quantum technology as exemplified by the quantum science satellite “Mozi” which took a lead in quantum-encoded communications.

By 2019 the Worldwide Threat Assessment report to the Senate by the US Intelligence Community had warned that the US lead in science and technology had been significantly eroded, largely because of China:

“For 2019 and beyond, the innovations that drive military and economic competitiveness will increasingly originate outside the United States, as the overall US lead in science and technology (S&T) shrinks; the capability gap between commercial and military technologies evaporates; and foreign actors increase their efforts to acquire top talent, companies, data, and intellectual property via licit and illicit means. Many foreign leaders, including Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin, view strong indigenous science and technology capabilities as key to their country’s sovereignty, economic outlook, and national power.”

The unwritten assumptions to the US-China relationship were that a) China would never challenge the US economically or militarily and b) as China became wealthier it would Westernise and adopt our institutions or at least move in that direction. But this hasn’t happened. I learnt Japanese and moved to Japan when it was still the second largest economy in the world. At one moment there was a fear in the US that Japan would topple the USA but in reality it wasn’t as much a threat as the talking heads suggested. And besides, they were always part of the US military bloc in the Pacific. They had no interest in promoting an alternative system. China is now seen differently.

Hong Kong’s Tough Year

My experience of Hong Kong was always that it was always an incredibly free place to live. It is a dream for a libertarian as the government pretty much leaves you alone as long as you pay your taxes and don’t commit any criminal offences. Its civil service and police force was always considered world class.

Last year protests erupted after the Hong Kong government tried to pass extradition legislation. It had no system to deal with foreign countries. However, democrats in the LEGCO and many of Hong Kong’s youth thought that such legislation might be used to have Hong Kong citizens sent to China. In the background, and as I have written elsewhere, one of the other reasons for the riots was the rising gap between the rich and the poor. We all saw the endless battles on our TV screens through the year, although you might not have seen some of the more extreme acts of violence perpetrated by the demonstrators as the foreign media’s editorial stance was very much in support of the rioters. The economy was hit hard in 2019, with the first recession for a decade, and then the Coronavirus struck. This year January – March GDP was down 8.9% y-y, the worst on record.

Finally, the Chinese government dropped a political bomb saying that its standing committee of the National PEople’s Congress (NPC) will be granted the authority to add clauses of a national security law directly into the Annex III of the Basic Law. Under Article 23 of the Basic Law Hong Kong’s (mini-constitution) which was agreed under the Sino British Joint Declaration in 1983, Hong Kong’s local government was obliged to pass national security related laws or more specifically: “shall enact laws on its own to prohibit any act of treason, secession, sedition, subversion against the Central People’s Government, or theft of state secrets, to prohibit foreign political organizations or bodies from conducting political activities in the Region, and to prohibit political organizations or bodies of the Region from establishing ties with foreign political organizations or bodies.”

Since the handover, there has been no national security law unlike most countries. So there has been seen a gap in the legislation. Presumably it didn’t rush to pass it after the handover in 1997 in order to avoid spooking sentiment. The local government tried to pass a law in 2003 but backed off. Some local Hong Kongese were worried that a national security law might be abused and mainland agents might abduct Hong Kong citizens to the mainland.

Other scholars think that this will end Hong Kong’s traditional rule of law (https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3086269/will-hong-kongs-rule-law-survive-challenge-beijings-national). However, many locals and foreigners living in Hong Kong I spoke to are relieved at the likelihood that the protests will soon stop.

The timing of this intervention into Hong Kong was interesting and explains a lot about US-China relations.

First, local sentiment is shifting according to my conversations. After the battering the Hong Kong economy received last year with the protests local citizens are getting tired. In 2019 there was a lot of sympathy for the protestors. But now after the Covid-19 shock, many businesses are really suffering economically. Furthemore, social media has been picking up on the violence used by protestors as well as evidence suggesting that there has been a lot of foreign meddling in local Hong Kong affairs. They are wondering whether there is some truth to the Chinese government accusations that many of the protestors were either influenced or funded by foreign agencies, think tanks and media. It has puzzled many Hong Kongese that foreign media haven’t covered both sides of the story.

Second, the global climate has shifted with the US upping the ante on multiple fronts including the new law (the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act), further restrictions on allowing Chinese firms using US semiconductors and accusations from the White House that a Chinese lab in Wuhan released the Coronavirus. I think the Chinese have made the strategic decision that negotiation here is tricky and a bold approach needed. They certainly seem to have more confidence than at any time since 1978 to push back against the West

If US-China relations worsen, I suspect that Hong Kong will end up being an arena for the disagreement. The Economist magazine wrote an article this week asking the question whether the city could retain its status as the world’s number 3 global financial centre after New York and London. It describes the US’ nuclear option:

“…in the back of some minds is the nuclear scenario, in which Hong Kong’s role as a financial hub is destabilised. By accident or design the American authorities could clog or cut the payments arteries by imposing sanctions, additional administrative requirements or penalties on individuals, firms or banks operating in Hong Kong. Any of these measures could seed concern that money parked in Hong Kong is no longer perfectly interchangeable with that in the West.

Viewed narrowly, America doesn’t have much to lose: less than 1% of its banks’ assets are in Hong Kong. But fully weaponising the financial system would be a huge escalation. Hong Kong might find it harder to protect its currency peg from capital outflows.”

The Asian or Chinese Century

China had a challenging start to 2020 with the outbreak of Covid-19. Some pundits were wondering whether this would be China’s Chernobl. In fact, it turned out that China’s shock and awe response to the pandemic seemed to be effective. And so far, many Asian nations have more effectively responded to the crisis without having to completely cease all commerce.

One has to wonder whether Covid 19 represents something more significant to the global order. Observing history one often sees that a major war marks or catalyses a shift in the dominant world power. This seems to have been true for thousands of years. The Spanish fell to the Dutch in 1581. Then the Dutch fell to the British in the Fourth Anglo Dutch War, powered by the Industrial Revolution in 1780. In 1919 at the Paris Peace Conference and the establishment of the League of Nations Woodrow Wilson’s vision of a New World Order was born and the USA became the global dominant superpower. After WW2, the USA represented more than 50% of global GDP.

Does Covid-19 mark the shift at least to an Asian Century, if not a Chinese Century? Already last year I remarked that in terms of GDP, 2020 could mark the year where Asia overtakes the rest of the world. According to the FT:

“The Financial Times tallied the data, and found that Asian economies, as defined by the UN trade and development body Unctad, will be larger than the rest of the world combined in 2020, for the first time since the 19th century.”

Hope for a Multipolar World

Last year I got to know and interview Kishore Mahbubani, a senior Singapore diplomat and former President of the UN Security Council. He expected the China-US relationship to worsen before getting better. Recently in the Economist magazine he took a bigger picture view of the future world order:

“The rules-based global order was a gift by the West to the world after the second world war. Will China overturn it when it becomes the world’s undisputed economic power, as it eventually will? Here is the good news. As the current, biggest beneficiary of this order (since China is already the world’s largest trading power), the country will preserve the rules. However China will systematically try to reduce American influence in international organisations. In early 2020 China put up a candidate to run the World Intellectual Property Organisation. America campaigned ferociously against her. In the end, a neutral candidate from Singapore won. This provides a foretaste of fractious battles to come.

The world after the crisis may see a hobbled West and a bolder China. We can expect that China will use its power. Paradoxically, a China-led order could turn out to be a more “democratic” order. China doesn’t want to export its model. It can live with a diverse multi-polar world. The coming Asian century need not be uncomfortable for the West or the rest of the world.”

Perhaps the US-China relationship has changed inexorably. But we might been in the transition to a more multipolar world with a number of influential powers including China, US, India, Russia, Japan, Turkey, UK, EU and Iran. This might not be such a bad thing for global peace.

And what of Hong Kong?

Hong Kong is likely to remain at the front line of US-China relations, at risk of being a geopolitical football. But the street protests at least should continue to abate. Longer term, there are huge opportunities in Hong Kong still but these will be for ones who are comfortable with the ‘One Country’ part of ‘One Country Two Systems’. In the worse case scenario, it will be a significant city and part of the Greater Bay Area in the worlds no 2 economy.